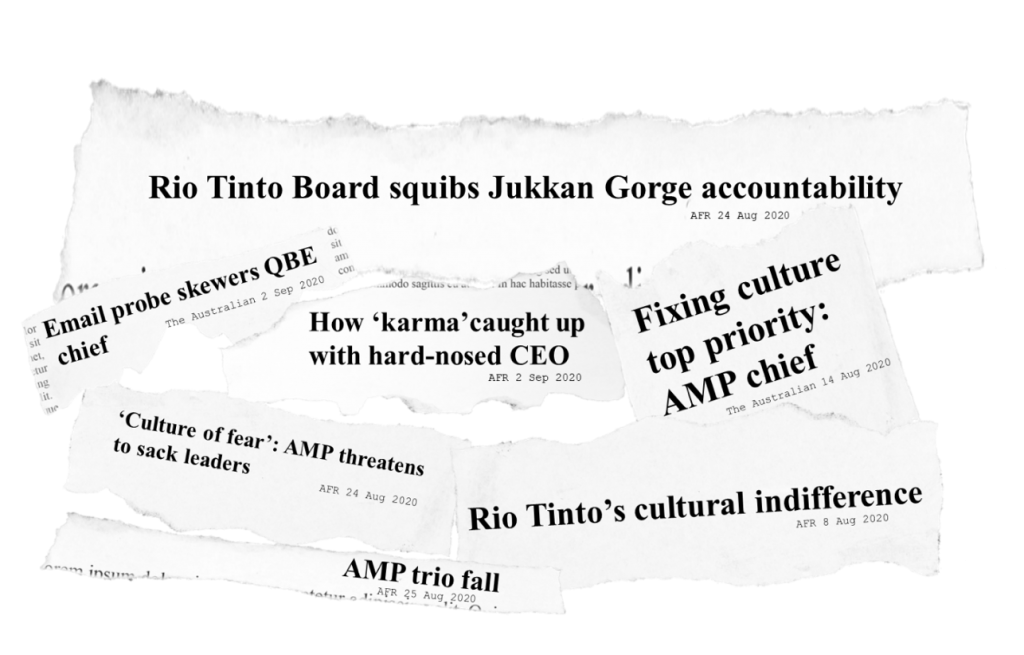

There has been considerable focus on workplace culture and conduct in Australia in recent months, traversing leadership, conduct, governance and decision-making.

Why does it take Royal Commissions, media reports, shareholder activism and litigation before boards and senior leaders recognise that issues of culture, and the behaviours it may engender, represent material risks to business outcomes?

As parents to the generation of ‘digital natives’, we worry about the social pressures and behavioural norms to which our children are exposed online. While ‘fitting-in’ has always been important to humans, our ubiquitous social technologies have brought a real-time, 24/7, and broadly distributed set of dimensions to the dynamics of social connectedness.

Most often, our concern is for behavioural proclivities that may lead youngsters to a ‘slippery slope’, triggering a cascade of undesired outcomes. Good parents seek to be proactive in managing children’s exposure to risks created by ‘peer pressures’, rather than waiting to learn of harm after injury and damage is done. So why do we not take that same mindset to how we regard culture and behaviour in the workplace?

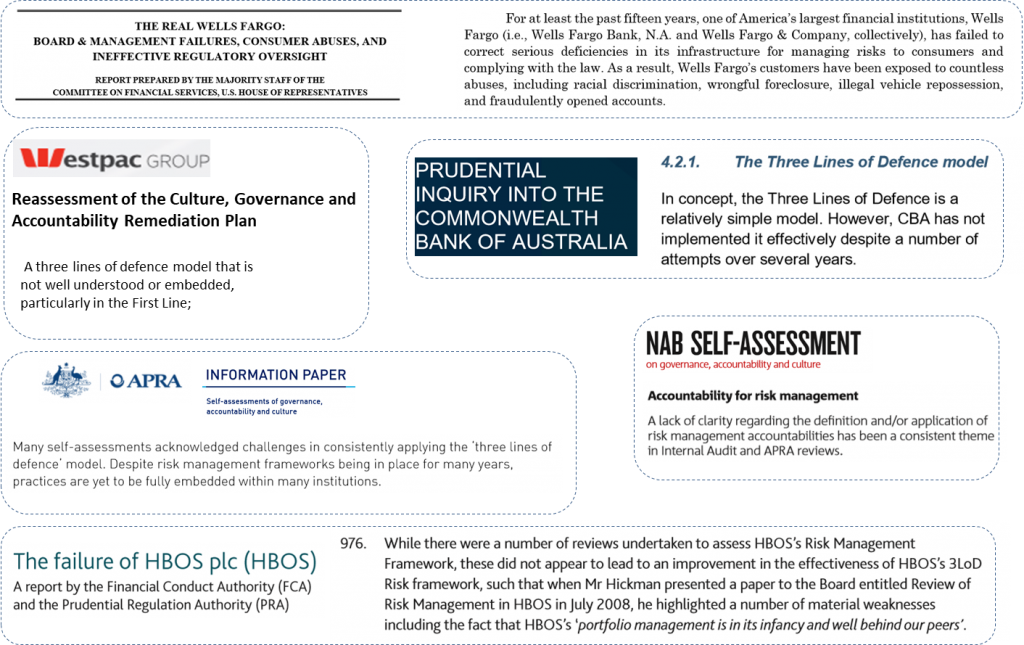

Non-financial risk management in the financial services sector is managed according to a Three Lines of Defence (‘3LoD’) model. This operational paradigm is as pervasive in the industry as social technologies are in our childrens’ lives. And similarly, there’s no shortage of dialogue on what widespread adoption of the 3LoD model may imply, and how the model must evolve to protect our interests more efficiently and effectively.

A majority of reported risk management failures lead to the conclusion that the 3LoD model was insufficiently well ‘embedded’ within a firm. Typical call-outs include: inadequate clarity in roles and responsibilities, coordination challenges, broken processes, and inaccurate risk reporting, collectively enfeebling the ‘voice of risk’ in the organisation. To us, the striking question is: why does this pattern of failure persist?

The model doesn’t manage risk, people do

Traditional risk management typically underweights our profoundly social nature. In all spheres of life, we operate within fundamentally social constructs, with informally defined expectations of behaviour guiding how we must act if we are to ‘fit in.’ Formal processes, systems and structures (including financial incentives) hold far less sway than does the social imperative of normative compliance – or, ‘going along to get along.’

Looking through a structural lens, one perceives structural solutions. This characterises our approach to risk management in the financial industry: we emphasise solutions of process and system. But if there are other factors at play – namely, social factors that system and process tweaks fail to contemplate – then we should not be surprised when structural solutions result in risk management failures.

At many firms, non-financial risk management has become little more than a Kabuki theatre, designed to provide comfort that things are taken seriously—without actually shifting things at all—and to produce demonstrable (if spurious) ’evidence’ of thoughtful activity to placate concerned stakeholders. Such false comforts are costly and produce immense frustration when risk management failures appear (as they inevitably do).

Spending on governance, risk and compliance systems, tools and processes across the global financial sector is estimated to exceed USD $100 billion annually. And, yet, firms continue to experience poor risk outcomes, resulting in the added expense of punitive fines and customer remediation. Estimates suggest that such added costs have exceeded USD $500 billion in the global aggregate since the GFC.

This circumstance exists because it is permitted to. Got the right inputs? (check) The right tasking? (check) The right systems and processes to support the tasking? (check) Are appropriate tasks being done? (check) By people ‘fit for purpose’? (check) Got good accountability mapping for those folks? (check)

Great! Did we get the desired outcomes? Uhhhmmm …

Distracted by Kabuki theatre offerings, attention from regulators, boards and leaders is focused on GCRA inputs, while outcomes are largely left to chance. It is of course far easier to frame attention in terms of what’s there—systems, processes, people—and away from the more important consideration of what’s not there—behavioural norms and social dynamics that produce a propensity for desired outcomes. If this approach to risk was a trading strategy, investors would rush to pull their money out of the fund. Yet such is the accepted state of non-financial risk management right across the Australian financial sector, catalogued exhaustively by the Hayne Royal Commission and news headlines.

When culture and conduct problems come to light, the industry’s reflexive response is to call in consultants. Firms should of course bring in expertise when it is lacking internally and, in the case of behavioural risk and culture, where independence brings objectivity. But, too often, firms instead seek to offload responsibility for risk management by outsourcing it to consultants who are happy to produce the same shelf-ware for all clients, and to be paid twice and thrice for the same intellectual effort.

Criticism of this over-reliance on consultants was resounding in the wake of APRA’s prudential inquiry into the Commonwealth Bank of Australia and the subsequent capability review of APRA. ‘Someone told me that cultural change takes 10 years’, Graeme Samuel said at the time. ‘The only [person] who would promote a 10-year program of cultural change is consultants brought in to implement it’.

Such consulting solutions are usually highly defensible – indeed, that is what they are designed to create: defensibility. Efficacy seems an afterthought. Regrettably, it is very easy to see how the current proliferation of ‘risk culture frameworks’ will lead industry down a similar garden path. More GRCA theatre is set to ensue.

Effective behavioural risk management

We don’t need better frameworks that help with more box-checking. We need real-time insights into cultural drivers of behaviour so that firms can course-correct when things look likely to hop the guardrails. If we fail to contemplate the established-yet-unspoken norms and cultural proclivities that permeate a firm, behavioural risks will go unidentified, unmanaged, and unmitigated.

We need real-time, evidence-based and data-driven insights that provide leading indicators of risk before it manifests, rather than backward-looking surveillance systems designed to catch bad actors after-the-fact. ‘More of the same, but better’ won’t cut it. And note, the approaches we call for need not be soft and fluffy, woolly, nebulous or intangible. By marrying behavioural science to data science, it is possible to devise quantitative metrics for the qualitative challenges of management — and to adopt approaches that enable proactive management interventions, targeted precisely, and applied in a more timely, efficient, and effective manner.

By deploying behavioural expertise and leveraging recent advances in network theory and machine learning, it is now possible to manage risk exposures from the front-foot and to unlock improved performance. Rather than waiting for risk to materialise and suffering through the inevitable backlash from investors, customers and a more deeply aggrieved public, leading firms (and their regulators) will invest in predictive approaches, including behavioural analytics, to drive proactive risk mitigation and meaningful operational resiliency.

Tamara Scicluna is an Executive Director at Rhizome

Stephen Scott is a globally recognised risk management expert and CEO of Starling, a US-based leader in the RegTech space

Disclaimer:

This communication provides opinions which are current at the time of production. The information contained in this communication does not constitute advice and should not be relied on as such. Professional advice should be sought prior to any action being taken in reliance on any of the information.